In the course of your research when looking to buy a rifle or pistol, odds are you’ve come across the terms “rimfire” and “centerfire,” used to define the type of ammunition a particular firearm uses. While more experienced shooters may toss these terms around loosely and with confidence, the terms warrant a bit of explanation for those new to the shooting sports. Ammunition for the modern rifles and pistols we use fall into one of those two categories, and it’s important to understand the differences between them.

Rimfire Cartridges

Rimfire cartridges contain their “priming compound” in the “rim” of the cartridge. The priming compound is what sparks to ignite the gunpowder within the cartridge case, while the rim is precisely where the firing pin strikes when the user pulls the trigger. The powder charge sits directly in front of the priming compound, so ignition is very reliable.

The beauty of the rimfire cartridges is in their simplicity. They are easily constructed, use a relatively small amount of powder, and generally generate low pressures. Those low pressures mean there’s not a lot of felt recoil for the user. Rimfire ammunition also produces less noise than most centerfire ammunition. If you participated in a First Shots event that introduced you to rifles or pistols, you had your first experience with a rimfire gun.

Trivia! Rimfire cartridges, the eldest of our modern, self-contained metallic cartridges, are generally the smallest cartridges we have. This wasn’t always the case. If you’ve ever seen the movie Dances With Wolves, Kevin Costner’s character used a Henry rifle, a rimfire. That firearm was chambered in the large .44 Rimfire. It packed a punch! But such a gun and ammunition are the exception to the “rimfire rules.”

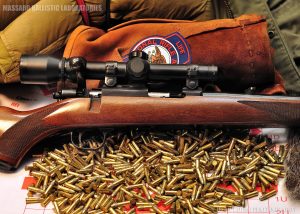

In today’s firearm world, the .22-caliber rimfires are invariably the most popular of the survivors of the rimfire era. This is especially true for the always-popular .22 Long Rifle round. The newer .17-calibers are coming in a close second these days. For instance, you may have been in a store or at a gun show and seen either the .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (HMR) or the .17 Mach II. These are very new cartridges (just developed in the past several years) that derived from the older .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire and .22 Long Rifle, respectively.

Centerfire Cartridges

Today’s centerfire cartridges are as different from their rimfire cousins as you could imagine. For one, they use a much thicker brass case. More importantly, they use a component called a “primer.” If you’ve looked at the bottom of a .45 ACP, .38 Special or .308 cartridge, you’ll see a button-like fixture imbedded in the center of the brass rim. That button is the “primer.” It is an individual component that, during the manufacturing process, is fitted into the brass case. Like the full rim of a rimfire round, the primer is what contains the priming compound. When struck by the firing pin when the user pulls the trigger to fire the gun, that priming compound in that primer is crushed against a part of the primer that’s called an “anvil.” That crushing sends a shower of sparks into the powder charge within the case.

Since centerfire cartridges use a primer that’s a component of the overall cartridge construction, they are inherently more complicated than rimfire cartridges. But wait, there’s more! Primers for centerfire cartridges come in different sizes and power levels. Small Rifle and Small Pistol primers measure 0.175-inch in diameter. Large Rifle and Large Pistol primers are 0.210-inch in diameter. There are also Magnum versions of each of these.

These sizes are important if you decide to “reload” centerfire cartridges at some point. Reloading is the art of using previously fired brass cases and reloading them with new primers, powder and bullets. It’s a great hobby that many sportsmen enjoy, especially serious competitors, hunters and avid recreational shooters, as reloading can improve accuracy and save money over buying new-in-the-box factory ammunition. Rimfire cartridges, on the other hand, are not reusable. Once a rimfire cartridge has been fired, the priming agent in the rim is used up and, because that priming agent isn’t in a primer that can be removed and replaced with a fresh primer, there is no way (at least not safely load them again with fresh powder and a bullet.

Centerfire cartridges come in an enormous range of size and power levels. These are .458 Winchester and .458 Lott cartridges, suitable for hunting large and dangerous game.

Generally speaking, centerfire cartridges operate at significantly higher pressures than do rimfire cartridges. That also means more recoil and a louder bang, but the benefits are that centerfire rounds generate considerably higher velocities than their rimfire counterparts, important when shooting at longer distances and for hunting.

There are fantastic firearms chambered for both types of cartridges. Rimfire cartridges make a wonderful choice for target practice, plinking, and small game hunting, while centerfire cartridges perform those functions and can also handle large game, long-range shooting duties and self-defense roles.

I have firearms of both types. In particular, I take advantage of the cost-effective traits of the rimfire cartridges in a rifle or pistol similar to others I have chambered for centerfire calibers. I spend more time practicing with the cheaper, lower-recoiling rimfires, saving my budget for the centerfires for perfecting technique and actual time hunting. I love big-game hunting with my centerfires, but I also enjoy the pursuit of squirrels, rabbits and smaller fur-bearing species with the rimfire rifles and pistols that I have come to enjoy so often. A shooter can spend hours at the range with little or no fatigue when using the rimfires, and it really is hard to beat a good .22 when it comes to a fun day at the range. The choice is up to you and your shooting requirements, but I’d be willing to bet you’ll end up owning both before all is said and done.