By Philip Massaro

“Dial up 21 MOA and give me one minute of wind left.”

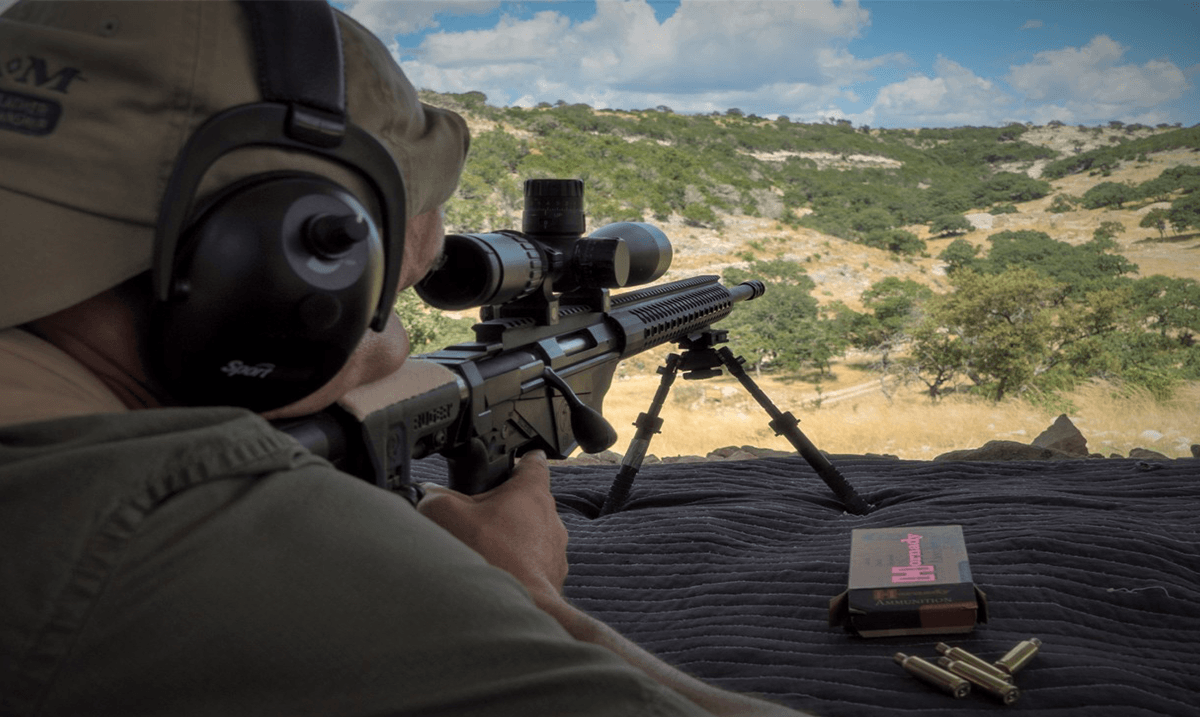

So came the instructions from the spotter, as we engaged the 750-yard steel plate. As I broke the trigger and saw the hit, I reflected upon just how much science goes into hitting a distant target.

The author has a spotter to help him correct the bullet’s trajectory while shooting at a steel plate 1,200 yards away.

Think of a baseball’s path as it leaves the bat of a power-hitter, travels high into the sky and comes down into the upper deck, resulting in a home run. That curve, the “trajectory of its travel,” is what your bullet’s doing in its flight to its target. Formally, trajectory is defined as “the path followed by a projectile flying or an object moving under the action of given forces.” That path becomes more drastically curved as the distance from the rifle’s muzzle increases and the effects of gravity have time to rear their ugly head.

Ah, gravity. It tugs at a bullet launched from your rifle, just as it pulls your furniture to the floor and your feet to the ground. In order to strike our target, then, we need to elevate the muzzle of the rifle in order to compensate for the effects of gravity. This is what creates an arced trajectory.

Fighting Gravity

Just how much the rifle’s muzzle needs to be elevated depends on several things. First is the shape and size of the bullet. (That shape in size collectively are known as “ballistic coefficient” or BC, but more about that in a minute.) The speed of the bullet, the distance to the target and the atmospheric conditions also play their parts. And the farther the target is from the muzzle, the more elevation will be required to compensate for gravity.

The shape of your bullet has a definite effect on trajectory; as you can see, there are many designs available for different applications.

Addressing the speed issue, I refer back to the idea that all objects (generally) drop at the same rate. Accordingly, the faster a bullet can travel away from the muzzle, the more ground it can cover before dropping a prescribed distance. This is the reason many magnum cartridges are described as “flat-shooting.” They possess a higher velocity and, therefore, the bullet launched will cover more distance before dropping, and the resulting trajectory curve is flatter than that of a slower cartridge.

For the long-range shooter, adjustments in trajectory must be made to compensate for the given atmospheric conditions in order to hit the target. Atmospheric drag is the defining factor here. Thick air will slow a bullet faster than will thin air. The air at sea level tends to be denser than, say, the air at 5,000 feet, so even with all other components being equal, your rifle will not give the same trajectory curve with the same ammunition at both elevations.

I mentioned ballistic coefficient a couple of paragraphs back. This is a unitless number that assesses a bullet’s ability to overcome air resistance during its flight. Long, sleek bullets that slice through the atmosphere easily maintain velocity far downrange and travel further with less drop, while a short, flat-nosed bullet will slow down faster and require a more drastically curved trajectory in order to strike its target accurately.

The higher a bullet’s BC, the better it will resist atmospheric drag. If we compare two bullets of the same caliber and weight having different ballistic coefficients but sharing the same muzzle velocity, the bullet with the higher BC value will give a flatter trajectory.

Putting it Together — And, Yes, There’s an App for That

To understand how all this talk about trajectory relates to your time at the range, you need to also need to know how to make them work with your cartridge’s ballistics. Let’s look at what my spotter told me to do with that 750-yard target.

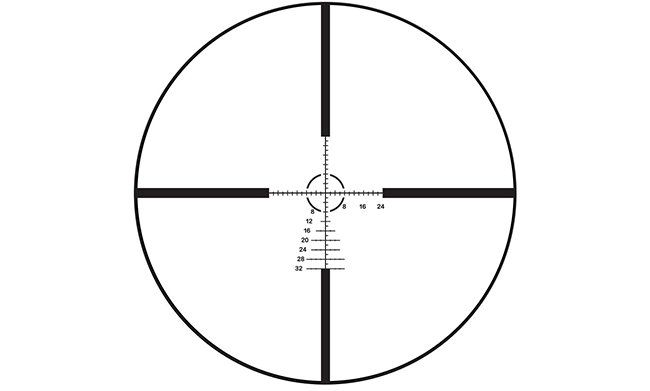

When he told me to “dial up 21 MOA,” he was talking about “minute of angle.” A minute of angle is a measure of arc equal to 1/60th of a degree, so, my spotter was telling me I would need to elevate my rifle’s muzzle — via a change in the position of the reticle in my scope — enough to make an angle of 21 minutes above the zero line to the target. This allowed for the amount the bullet would drop by the time it reached the target 750 yards away. Starting to see how this ties together?

The rifle I was using for that shoot was chambered for the popular 6.5 Creedmoor cartridge, and the scope on top had precise graduations that allowed me to precisely dial the necessary amount of elevation. Had I been using a cartridge with less velocity or with a bullet of lesser ballistic coefficient, the amount of elevation needed would have been more.

A ballistic calculator like this Kestrel unit and a good rangefinder like this Bushnell Con-X will give the necessary data to adjust your trajectory.

The data for my particular load, at that particular distance, was obtained from one of the many ballistic calculators available (I happened to be using the Hornady 4DOF program), which gave us information on trajectory, wind drift and many other factors useful to making the shot.

Today’s Distance Cartridges

The most popular target cartridges are popular for a couple reasons. They deliver a flat trajectory, usually using a bullet with a high BC, and they offer a recoil level that is tolerable to most shooters. Noteworthy magnum cartridges deliver higher-than-normal velocities and, thereby, flatter trajectories, but that comes with heavier recoil. (That can be mitigated with the use of a muzzle brake, but then there’s premature barrel wear.)

The popular 6.5 Creedmoor has the desired characteristics for a long-range cartridge: low-recoil and a sleek bullet.

The .308 Winchester, 6.5 Creedmoor and 6 Creedmoor are examples of cartridges that represent a fantastic balance of long-range capability, flat trajectory and low recoil. The .300 Winchester Magnum, 6.5-284 Norma, 6.5 PRC and .338 Lapua offer heavier bullets, higher velocities or both, again with the price of increased recoil.

When it comes to distance target shooting, there is no cartridge that will shoot perfectly “flat.” All need muzzle elevation. Whether you use the elevation turret on your riflescope to make the adjustment or use a scope with a graduated reticle to measure the amount of elevation or holdover and achieve that trajectory is up to you, but you’ll need some means of precise measuring for successful distance shooting.

A top-quality riflescope like this Leupold Mark 4 has an elevation turret with precise gradations to allow the shooter to adjust for varying distances.

Just as an outfielder in baseball needs to elevate his throw in order to reach home plate, at distance the shooter must elevate the shot in order to hit the target. Knowing just how much to do that — and ultimately understanding the trajectory of your rifle — is paramount to hitting your target. Download a good ballistic calculator and take a look at how different bullets for your chosen cartridge perform at varying ranges. The more familiar you become with the trajectory of the cartridge and bullet combination you’ve chosen, the better a rifle shot you’ll become.

About the Author

Philip Massaro is a freelance writer whose passions include big game hunting and ballistics. He has appeared on numerous outdoor television programs and has authored books on both hunting and ballistics.

You may also be interested in:

- Why is Parallax Adjustment Important? - Rifle Scope Tips with Ryan Cleckner

- Scope Turrets - Rifle Tips with Ryan Cleckner

- Understanding the Parts of a Scope - Rifle Tips with Ryan Cleckner

- Intro to Scopes - Rifle Tips with Ryan Cleckner

- Transonic Range | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- What To Look For In An AR15 | MSR Shooting Tips with Ryan Muller

- M16 Rifle | The Gun Vault - Cody Firearms

- Dealing With Obstructions | Cleaning and Maintenance Tips

- Long Term Storage | Cleaning and Maintenance Tips

- How To Clean Your AR-15 | Cleaning and Maintenance Tips

- Off-Hand Shooting | MSR Shooting Tips with Ryan Muller

- Reverse Kneeling Position | MSR Shooting Tips with Ryan Muller

- Cable Systems and Bore Guides | Cleaning and Maintenance Tips

- Springfield 1903 - The Gun Vault #22 - Cody Firearms Museum

- Reloading Your Rifle | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Canted Shooting | Precision Rifle Shooting with Todd Hodnett

- Using A Rear Bag | Precision Rifle Shooting with Todd Hodnett

- Alternate Range Zero - Long Range Rifle Shooting with Tod Hodnett

- Winchester 1873 | The Gun Vault - Cody Firearms

- Hawken Rifle | The Gun Vault - Cody Firearms Museum

- Head and Scope Position | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: Atmospherics and Ballistics Calculators | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Prone Position: Getting Set on the Rifle | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Hemispheric Distortions | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Power Down Your Optics | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Reading Wind with Optics | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Kneeling and Using Rests | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Shooting Supports | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Rifle Sling Tip | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Shooting From The Knee | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Variable Optics and Walking | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Setting Up Binoculars | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- AR-10 Press Check | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Two-Stage Triggers | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Shooting Error: Rifle Cant | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Safety Selector Tips | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Precision Rifle Pistol Grip | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Mixed Terrain Obstacles | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Acceptable Accuracy | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Bipod vs Bag Shooting | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Finishing Shooting | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Correcting Bad Habits | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Trigger Control | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Running the Bolt | Long-Range Rifle Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: Ballistic Coefficient | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- The Ultimate Rifle Tip: Real Time Zeroing with Ryan Cleckner | Long-range Shooting

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: Training | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: Ballistic Solvers | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: Ammunition | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: The Scope | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: The Rifle | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Calibrating Your Ballistic Solution | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Setting Up Your Rifle | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Equipment Advice | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Purpose Built Rifles | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Shouldering a Rifle & Eye Dominance - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Chris Cheng

- Large Caliber Rifles | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Understanding Rifle Sights and Optics - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Chris Cheng

- Beginners Guide to Handling Rifles Safely - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Champion Chris Cheng

- Hand Loading | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- How to Load a Rifle - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Chris Cheng

- Terminal Bullet Performance | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Rifle Grip & Stance - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Chris Cheng

- Advanced Bullet Stability | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Bullet Basics: What's Inside a Rifle Cartridge? - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Chris Cheng

- Bullet Stability & Twist Rates | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Top Factors for Hitting the Target | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Rifle Basics: Actions - Rifle 101 with Top Shot Chris Cheng

- What Is "Long-Range" Shooting | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- A Closer Look at the AR-15 Platform - Modern Sporting Rifle Facts

- Elements of Long-range Shooting: Coriolis Effect | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Elements of Long-Range Shooting: Spin Drift | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Elements of Long-Range Shooting: Aerodynamic Jump | Applied Ballistics

- Elements of Long-Range Shooting: Muzzle Velocity | Applied Ballistics

- The Science of Accuracy | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- ¿Qué Puede Esperar Cuando Va Al Polígono De Tiro? | What To Expect When Going to the Shooting Range

- Scope Tracking: Tall Target Test | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Accuracy & Precision Defined | Applied Ballistics with Bryan Litz

- Teamwork: Spotter & Shooter - Long Range Rifle Tip

- Trace - Long Range Rifle Tip

- Rifle Cleaning - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- AR-15 Maintenance: Field-strip, Clean and Lubricate an AR-15 - Gunsite Academy Firearms Training

- Shooting Positions in the Field - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Shooting Fundamentals - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Scope Tracking Drill - Long Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Practical D.O.P.E. - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Rifle Sight-in Process - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Shooting at Angles - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Wind Estimation and Compensation - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Understanding Mils (Milliradians) - Long-Range Shooting with Ryan Cleckner

- Understanding Minute of Angle (MOA) - Shooting Long Range with Ryan Cleckner

- How to Mount a Rifle Scope | Shooting Long Range with Ryan Cleckner

- Shooting Fundamentals and the AR-15: Modern Sporting Rifle Tip - Modern Defensive Training Systems

- Stance and the AR-15: Modern Sporting Rifle Tip - Modern Defensive Training Systems

- AR-15 Administrative Load and Unload: Modern Sporting Rifle Tip - Modern Defensive Training Systems

- Two-Shot Sight-In: How to Zero a Rifle in Two Shots - Rifle Tip

- Using A Sling to Stabilize Your Shot - Rifle Tip

- Accessorize Your AR-15: Modern Sporting Rifle Tip - Modern Defensive Training Systems

- Clean your AR-15 - Modern Defensive Training Systems

- Rifle Cleaning and Lubricating Basics - Gunsmith Tip

- Faster Twist Rates | Precision Rifle Shooting with Todd Hodnett

- Competition Setup | MSR Shooting Tips with Ryan Muller

- Positional Shooting Fundamentals | Precision Rifle Shooting with Todd Hodnett

- AR Reloading | MSR Shooting Tips with Ryan Muller

- Basic AR Maintenance | MSR Shooting Tips with Ryan Muller

- How to Mount a Rifle Scope: Rifle Scope Tips with Ryan Cleckner

- How to Mount a Scope Part 4: Troubleshooting | Rifle Scope Tips with Ryan Cleckner